In her comprehensive biography, The Invention of Nature (Alfred A. Knopf, 2016), Andrea Wulf tells how Alexander Humboldt (1769 -1859) was the first to understand that the natural world “was interwoven as with ‘a thousand threads’.” Humboldt saw “unity in variety.” He was the first to consider different plants, animals and inanimate nature interdependent and unified in a global sense instead of each cataloged as discrete entities.

Reading Humboldt’s biography reminded me about when my father considered a bicycle wheel a metaphor for unifying diversity. “Look,” he said as he sketched a wheel, “many discrete spokes can be traced back to the same central hub.”

Humboldt saw the world as the ‘hub’ and all the natural entities as the ‘spokes’. Later, Charles Darwin famously linked discrete species to create one evolutionary tree for all the species: the ‘spokes’ were the different species that were unified by being traced to their ancestors on the same ‘hub’, which was the evolutionary tree. An extreme and surprising evolutionary connection (known as a deep homology) between the ray fins of fish and hand digits of mammals, two structures previously thought to be unrelated, was reported today in the New York Times.

Instead of separate spokes leading into a common hub as a metaphor for unifying distinct entities, as described above, I find it interesting to consider a different perspective of the same image: the hub as a common source that radiates spokes rather than the sink receiving the spokes. The view of the hub as the source of the spokes – a metaphor for diversity exploding from a point – seems at first conceptually similar to tracing the spokes back to a common hub, like two sides of the same coin. However side A in the wheel diagram (sketched here) showing discrete spokes flowing into the central hub differs from side B, which shows spokes radiating from the hub. The two perspectives are not conceptual mirror images; they are not the flip sides of the same coin.

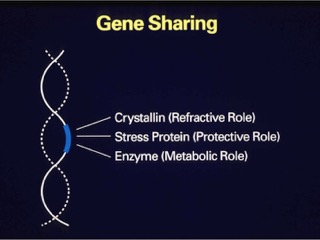

My research on genes expressed in the eye lens is an example of side B of the wheel diagram – diversity generated from a single source – and is illustrated schematically in the other figure shown here entitled ‘Gene Sharing’. I coined the term gene sharing for a single gene (a ‘hub’) producing a protein that has several unrelated molecular functions (the ‘spokes’). The hypothetical gene colored blue in the figure represents a gene producing one of the numerous proteins (known as crystallins) expressed highly in the lens. The functions of the crystallin proteins allow the lens to focus images on the retina in the eye. In addition, some crystallin proteins can protect other proteins under stressful conditions such as heat, and others have a metabolic role. These three functions – vision, heat protection and metabolism – are totally unrelated to one another. Gene sharing is a widespread phenomenon where one gene (a hub) generates a protein with multiple functions (the spokes). More about gene sharing can be found in my book, Gene Sharing and Evolution (Harvard University Press, 2007).

Both perspectives (side A and side B) shown in the wheel diagram could serve as metaphors for basic research, but the processes involved are not the same: ‘spokes into the hub’ portrays unity from diversity, while the ‘hub radiating spokes’ portrays diversity from unity. It would seem that the ‘spokes into the hub’ metaphor is more restricted to basic research – free exploration such as evolution – than the ‘hub radiating spokes’ metaphor, which includes applied research directed to finding diverse uses for a phenomenon.

Leave A Comment