Historically, Inuit art comprised small amulets carved from bone or ivory or derived from other natural substances. However, the Inuit apparently also carved stones as pastime and children’s toys, but this seems to have been a well-kept, though unintentional, secret to most of the world. The artist James Houston discovered these treasures when he visited the Arctic in 1949 and organized a major exhibit of Inuit art in Montreal.

Imagine – one man, one exhibition, and the new field of commercial Inuit art launched! But that’s what happened. The pieces essentially sold out in a few days – a few thousand stone and caribou antler and walrus ivory sculptures carved by Inuit no one ever heard of found new homes in foreign lands in the blink of an eye. Inuit art was on the map, the art world enlarged. Houston returned to the Arctic where he lived for a number of years, developing the field of Inuit art, cultivating an artistic garden he discovered.

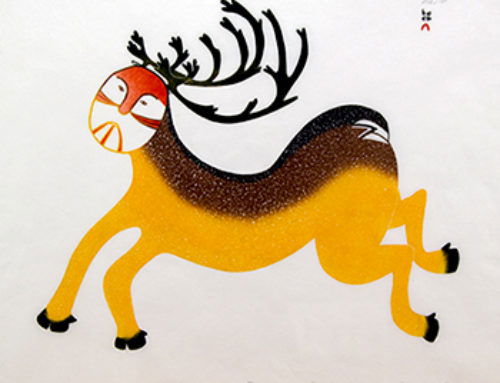

Many Inuit sculptures depict animals and lifestyle in the Arctic, which are easy subjects to comprehend within our experience. We are familiar with polar bears, seals, caribou, birds and other species, as well as with common activities, such as hunting, wrestling, giving birth, family life and the like. However, myths that are foreign to our experience also provide a major focus of Inuit art.

The most widespread Inuit myth is that of the Sedna or mermaid (part woman, part fish), who was Goddess of the Sea. In an earlier blog I sketched the essence of one of many versions of the Sedna myth (Jellyfish in Art), in which an unhappily married young woman living on an island with her dog-husband is rescued by her father. When her husband discovers that she is missing, he transforms into a bird, finds her escaping in her father’s kayak and flaps his wings creating waves to capsize the boat. Her father tosses her overboard and chops off her fingers as she clings to the side for dear life. I know, horrible! But here’s the remarkable part: the parts of her fingers and hands become the mammals of the sea. She sinks to the bottom, grows a fish tail, and becomes the powerful Sedna, the ruler of marine life and the provider of food and natural products extracted from sea mammals.

Neither the Sedna legend or other Inuit folklores are limited to single versions, possibly due to the fact, in part, that they are passed down by oral tradition through the generations and in part that they are perpetuated in different areas of the Arctic. In a slight variation of the Sedna myth, the young girl rejects potential husbands found for her by her father and marries a dog. Infuriated, her father throws her into the sea from his kayak and cuts off her fingers when she tries to climb back on the boat; the rest is as above.

In a different variation, when the maiden rejects all marriage proposals, a hunter appears, and her father agrees to trade his daughter for fish. He sedates her with a sleeping potion and gives her to the hunter, who takes her to his nest on a cliff, since he is a bird-spirit. Her father rescues his daughter in his kayak. Her angry bird-spirit husband creates a storm, her father throws her into the sea, and she hangs on the kayak. Her fingers freeze, fall off and become the sea creatures; she sinks and becomes the Sedna. In this version, there is no dog involved.

In still another version, a girl grows bigger than her giant parents. When she needs more food than is available, her parents bundle her in a blanket, take her out to sea in their kayak and dump her. The sea mammals and fish come from parts of her huge hands that are sliced off when she grasps the canoe. She falls to the sea bottom, becomes the Sedna and lives in a hut made by fish.

The Sedna’s father doesn’t give her away in other versions. In one theme, she is kidnapped by a bird creature, who imprisons her in a floating ice-island. However, once again, her father rescues her in his kayak and throws her overboard to appease the angry god. He chops off her fingers and so forth.

There’s even a version where the girl is a mistreated orphan and thrown into the sea after her fingertips are cut in order to drown her. The fingertips transform into seals and walruses, she marries a sculpin and lives in the sea as the Sedna controlling all the sea mammals.

Although the versions of the legend differ in detail, Sedna is always the source and ruler of marine life, and she is always worshipped by hunters and fishermen, who depend on her to supply food. She is the great provider, the mythological God. When seals and marine animals are scarce – a cause of impoverishment – Sedna is angry and marine life is entangled in hair. In prosperous times, her hair is flowing.

The Sedna myth has inspired Inuit artists, who have perpetuated and glorified her with innumerable sculptures based on her origin and role as provider. Any collection of Inuit art has works connected with the Sedna.

I present here a few Sedna sculptures from my collection.

David Ruben Piqoukun, a renowned Inuit artist, sculpted Sedna carrying a two-headed dog on her back, one white representing the ancestral white man and the other dark representing the ancestral First Nations people. This complex myth has several versions, each connected with the Sedna marrying a dog. In one version, the girl's father said that his daughter, who refused all marriage proposals, should marry a dog, resulting in her being impregnated by one. In an alternative version, she in impregnated by a dog disguised as a handsome stranger who comes to the. In both versions, she is abandoned on an island, where she gives birth to a combination of dog and human children. She puts the dog children in a boot made of sealskin and they drift out to sea and become the ancestors of the white man; she puts her human children in another outer sole of a boot, sets them out to sea, and they give rise to the Chipewyan Indians. Some Inuit claim that the European and First Nations people are descended from the dog children, creating the basis for their relationship to the Inuit people.

Photo by Michael Kingsberry, Select Cut Media LLC

A sweet depiction of the pre-Sedna sleeping with her dog-husband is represented in this sculpture by an unknown artist.

Photo by Michael Kingsberry, Select Cut Media LLC

One of the dog children by an anonymous artist is shown in this sculpture.

Photo by Michael Kingsberry, Select Cut Media LLC

A powerful sculpture by David Ruben Piqoukun shows the father, frightened by the waves caused by his daughter's angry husband, chopping off the fingers of his daughter while she clutches on the side of the boat. Parts of her fingers and hands become the mammals of the sea.

Sedna is seen as a provider for the people, most frequently of fish. This sculpture by Aqjangajuk Shaa shows Sedna holding a fish above her head.

Photo by Joram Piatigorsky

In a sculpture by David Ruben Piquokun that he showed in his one-man exhibition in 1995 entitled between two cultures (that of the white man and of the Inuit), he shows Sedna offering government housing instead of fish! The side of her face shown, with a white eye and no scarification, is that of the white man; the other side, not shown, is that of the Inuit, and has a red eye, scarification and an animal ear.

Photo by Michael Kingsberry, Select Cut Media LLC

In another sculpture by David Ruben Piquokun, Sedna offers knowledge, since she sees everything with her three eyes and tells all with her two mouths. She is embracing the egg of all knowledge.

Photo by Michael Kingsberry, Select Cut Media LLC

A famous story of Sedna is that she has been washed ashore and needs someone to get her back into the sea. An Inuk passes by and she persuades him to use a stick to roll her to the water, which is does. This is shown in the sculpture by Davidialuk Alusua Amittu, the major story-teller artist of the Inuit.

Photo by Michael Kingsberry, Select Cut Media LLC

Once she is in the sea, Sedna wants to reward her savior. “Come back tomorrow,” she says, “and I’ll have gifts for you.”

“No need,” he replies.

“Yes, please come.”

He does, and Davidialuk’s sculpture shows that she has brought him three presents: a sewing machine (abstractly shown on her back), a rifle and a gramophone. Each of these three items changed the life of the Inuit people. She is still a provider, but not fish this time.

Photo by Joram Piatigorsky

A beautiful sculpture by Davidialuk that I especially like but can’t relate to a particular story (although there may be one) shows Sedna holding her tail and that of her child swimming behind her.

Photo by Michael Kingsberry, Select Cut Media LLC

Sedna creeps into many stories, including Greek mythology, as shown in the small sculpture called Sea Spirit by Mattiusi Naulituk. This Sphinx-like sculpture from the Sugluk area of north Quebec draws on the Persephone and Demeter myth and archaic archetype of the Great Mother.

Photo by Michael Kingsberry, Select Cut Media LLC

Finally, Bill Nasogaluak sculpted Sedna being crucified. I am uncertain if this means that Christianity, which had a great influence in the Arctic, has crucified the Inuit God Sedna, or, more likely, Sedna is the Inuit God, as Jesus is the Christian God.

Photo by Michael Kingsberry, Select Cut Media LLC

David Ruben Piqoukun, a renowned Inuit artist, sculpted Sedna carrying a two-headed dog on her back, one white representing the ancestral white man and the other dark representing the ancestral First Nations people. This complex myth has several versions, each connected with the Sedna marrying a dog. In one version, the girl's father said that his daughter, who refused all marriage proposals, should marry a dog, resulting in her being impregnated by one. In an alternative version, she in impregnated by a dog disguised as a handsome stranger who comes to the. In both versions, she is abandoned on an island, where she gives birth to a combination of dog and human children. She puts the dog children in a boot made of sealskin and they drift out to sea and become the ancestors of the white man; she puts her human children in another outer sole of a boot, sets them out to sea, and they give rise to the Chipewyan Indians. Some Inuit claim that the European and First Nations people are descended from the dog children, creating the basis for their relationship to the Inuit people.

Photo by Michael Kingsberry, Select Cut Media LLC

A sweet depiction of the pre-Sedna sleeping with her dog-husband is represented in this sculpture by an unknown artist.

Photo by Michael Kingsberry, Select Cut Media LLC

One of the dog children by an anonymous artist is shown in this sculpture.

Photo by Michael Kingsberry, Select Cut Media LLC

A powerful sculpture by David Ruben Piqoukun shows the father, frightened by the waves caused by his daughter's angry husband, chopping off the fingers of his daughter while she clutches on the side of the boat. Parts of her fingers and hands become the mammals of the sea.

Sedna is seen as a provider for the people, most frequently of fish. This sculpture by Aqjangajuk Shaa shows Sedna holding a fish above her head.

Leave A Comment