Click the play button above to load an interactive version of John Tiktak’s Family

Imagine, the World Bank is exhibiting my collection of Inuit sculptures for a month! What a great satisfaction to see my hobby – collecting Inuit art, a labor of love – become a worthy contribution. I’m confident that those witnessing the exhibit will appreciate the skill of the artists and sheer beauty of the sculptures as well as learn about the fascinating Inuit culture in the Arctic. I hope that this exhibit helps these important Inuit artists, virtually unknown to most scholars and lovers of art, become more widely recognized, as they deserve to be, and that the artists (often known by a single name) represented in the exhibit – Osuitok, Tiktak, Davidialuk, Pangnark, Ruben, Nasogaluak, Anghik, Iksitaaryuk, Ennutsiak, Qiyuk, Equalla, Isaaci, Kellipalik, Kiawak, Qiatsuq, Talirunili, Ugyuk, Judas, Sallualu, Latcholassie and Oviloo – become familiar and join the ranks of other famous artists throughout the world.

Here are the opening remarks I gave to more than 100 people as well as those by Bernadette Driscoll Engelstad, an authority on Inuit art:

Thank you all for coming.

Thank you all for coming.

It’s exciting for me to see what started as an attraction, became a passion and developed over 30 years into a collection. In a way it’s like raising a child and see it develop into a successful, independent life of its own. It started like this:

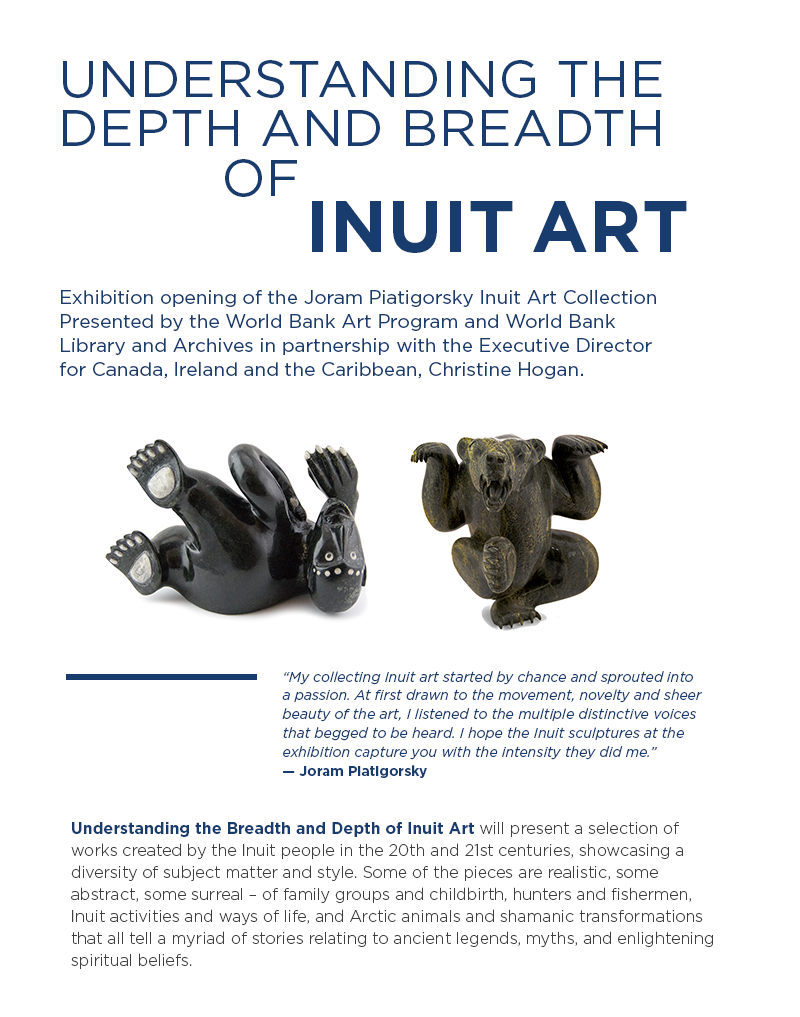

Strolling along after a day’s skiing with my family in Vail I passed a gallery with beautifully shaped sculptures of green and black stones and caribou antlers and marine ivory and musk ox horns and whalebone in the window. The group dazzled me. What most caught my attention was the incredible movement inherent in the carvings. They weren’t standing still; they were alive. I went inside the gallery and didn’t know where to look first – it was like being surrounded by dozens of dancers in a theater I didn’t know existed. These weren’t souvenirs; they were fine art. I picked up a small bear carving. The store owner smiled. He saw immediately that by touching I connected with that little bear. In my hand, the bear melded with the artist. I think Helen Keller was right when she said that touch was the most important sense.

I collected bit by bit, read about the Inuit and learned initially from my friend, John Burdick, who had one of the few Inuit galleries in the United States and is here tonight; he also had an Inuit art exhibit in Washington almost 20 years ago. As my collection grew I discovered that these magnificent works were far more than an aesthetic experience: they were an artistic microcosm filled with values both that I hold dear and that were new to me – about the centrality of family and cooperation, about playfulness and humor of daily life, about music, about ancient legends and myths that formed the foundation of Inuit culture, and about spirits and spiritual beliefs. Animals and humans were seen as an interacting continuum of body and soul, underlying mutual respect for one another. The many sculptures of shaman were chimeras of humans and animals, perhaps a bird with a human face or even a whale with caribou antlers, transformations of the shaman into the animal and back again, sharing their respective powers. This appealed to me as a scientist with an interest in evolution, for all animals are indeed our cousins, and the Inuit expressed this with skill, uncanny intuition and imagination in their art.

One of the most interesting aspects of Inuit art to me was its unexpected diversity, which all came from a homogeneous, frigid environment that’s dark for the much of the year. In this exhibition, the sculptures of the leap frog game and roaring bear and caribou are starkly realistic, the lonely Inuk with scratches for a face that appears at first sight no more than a small rock, the fanciful creatures as surrealistic as a Salvador Dali painting, the jet plane with a white pilot bombing bottles of alcohol on the Inuit and the angry Sedna portraying the dangers of global warning screaming lessons we should all heed. Each Inuit artist in this exhibit has a strong artistic voice that trumps the subject matter. In the same way that one can recognize a Van Gogh painting or Giacometti sculpture from afar – both household names among artists – one can recognize a Davidialuk or a Pangnark or a Talirunuili sculpture by style as well as subject.

I am deeply grateful to the World Bank for bringing these wonderful Inuit artists to your attention, for they deserve to enrich your lives as they enriched mine.

More information about Inuit art can be found in my website blogs, packets of postcards distributed here and my memoir, The Speed of Dark, just published, where I say more about my collecting Inuit art in the context of my life as a scientist surrounded by art.

Enjoy the exhibit!

Fighting the Giant by Davidialuk Alasua Amittu

Bernadette Driscoll Engelstad

Welcome to the Feast! A feast of the eyes!

For those of you familiar with Dr. Piatigorsky’s collection of Inuit art, you know that this is a small — yet carefully chosen – selection. Curated with an eye to Quality . . . quality in the works selected and the artists represented. Each sculpture in its own distinct way exhibits a mastery of material and artistic vision. Yet Joram might have made a completely different, equally fine selection of works from his collection – a fact that reflects Joram’s extensive knowledge and insight as a collector as well as the range of conceptual themes explored by Inuit artists across Arctic Canada.

Bird Shaman by Latcholassie Akesuk

As you wander the exhibit, think of these art works as both Art and Work – because for many decades – from the 1950s through the 1980s – art defined the local economy of the North. In the 1950s and early 60s, Inuit families were just beginning to come in from their hunting camps, settling in small communities with schools and nursing stations gradually established by the Canadian government. The transition from an ancestral way of life perfected over thousands of years of living in the Arctic – moving nomadically to hunt caribou, walrus, whales and seals – to a cash economy was abrupt and unexpected. With few jobs in the settlements for unilingual adults, and no real infrastructure for local employment, men and women turned to carving, drawing, and printmaking to support their families.

Art production provided hunters with time to hunt and cash for petrol, rifles, ammunition, boats and snowmobiles. Women’s income from art and craft production was often used to help with hunting expenses for their families.

Beyond opening our eyes to the mythology and spiritual beliefs of Inuit, as well as the social and cultural practices that have shaped Inuit life through the millennia, this exhibit bears witness to the resourcefulness and resilience of individuals, and of Inuit society as a whole. From stone, ivory, antler and whalebone, the artists before us have created impressive works of art out of materials close at hand, transforming the physicality of these materials in surprising and meaningful ways.

From Ennutsiak’s playful yet perfectly balanced gymnasts; Davidialuk’s tight cluster of figures overtaking a giant; David Ruben’s depiction of Sedna (Nuliajuk) – her father in the boat above with his knife raised, ready to sever the joints of her fingers which will give rise to the sea mammals on which hunters depend — Oviloo Tunnillie’s grief-stricken mother and child; the formal – one can only say ‘dignity’ — of Latcholassie’s Owl Shaman; and the delicate, if improbably poised Hawk by Osuituk.

It is fitting that these works – works of power and creative vision – were brought together by Dr. Piatigorsky who has spent an eminent and rewarding career researching the scientific basis of vision . . . and who shares with us today the human and humane vision of Inuit artists.

As you explore the exhibit, take note of the communities from which the artists come. From Povungnituk in the East to Tuktoyaktuk astride Canada’s border with Alaska in the West — with intermittent stops at Cape Dorset (Kinngait), Arviat, Baker Lake (Qamannituaq), and Gjoa Haven. This is a journey across Arctic Canada. It is also a journey across time . . . from works by early masters, including Eli Sallualu, Joe Talirunili, John Tiktak, and Pangnark, to a younger generation who tell their own stories, often focusing a critical eye on the life changes they have experienced and which have impacted Inuit families, communities, and the environment in such a critical way.

Over the next few weeks, I encourage you to spend time with these artists – and to share the exhibit with others. Although once a remote frontier, the Arctic is now a key focus of global attention. Long a society of oral tradition, through the dedication of artists, many represented here, Inuit have created an impressive visual tradition – a tradition of stories and life experience. As commerce and tourism gain an ever-stronger foothold in the Arctic, Inuit sculptors, graphic artists, musicians, filmmakers, and writers continue to offer much-needed insight into ways of knowing, appreciating, and preserving this extraordinary gift of our planet.

Today, Facebook serves the Arctic as a Museum without Walls where commercial art galleries, collectors, and museums post images of Inuit art to the delight of Northerners. Hopefully, there will someday soon be museums and cultural centres in every community across the Arctic where Inuit can view first-hand the art work of their peers and elders. Perhaps this exhibit can lay the groundwork for just such an undertaking!

In closing, we have but one thing to say to Joram and Lona Piatigorsky for the gift of this moment – Quyanamik . . . Thank You!

Bernadette Engelstad is an independent curator of Inuit Art & Cultural History, and a research collaborator at the Arctic Studies Center of the Smithsonian Institution.

Leave A Comment