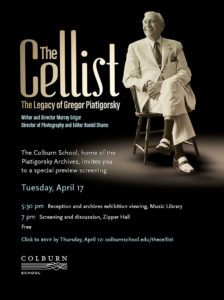

On April 17 next week, Papa’s birthday, I will be at the Colburn School of Music in Los Angeles to see a preview of the new documentary of my father: The Cellist: The Legacy of Gregor Piatigorsky, by Murray Grigor and Hamid Shams. The movie will be an important addition to the Piatigorsky Archive at Colburn of my father’s legacy as a renowned 20th century cellist.

On April 17 next week, Papa’s birthday, I will be at the Colburn School of Music in Los Angeles to see a preview of the new documentary of my father: The Cellist: The Legacy of Gregor Piatigorsky, by Murray Grigor and Hamid Shams. The movie will be an important addition to the Piatigorsky Archive at Colburn of my father’s legacy as a renowned 20th century cellist.

Papa would have been 115 this year, but sadly he died of lung cancer at 76. A life-long habit of smoking caught up with him, no doubt starting early when he supported his family as a pre-teen after his father abandoned his family. He suffered pogroms in Russia and then poverty in Poland and Germany as a refugee from the Bolshevik Revolution, endured pressures of concertizing throughout the world, barely out of adolescence – stateless, protected only by a Nansen Certificate of Identity – and narrowly escaped Nazi tyranny to America, where I was born.

Forty-two years since his death may seem like a long time, but I can still hear him saying to me (in his Russian accent), “People who… spend their life with beautiful things must have something beautiful in themselves.”

That sentiment is how I start my memoir, The Speed of Dark, which will be published this year by Adelaide Books:

Papa held his Stradivarius cello high with his arm extended, his hand gripping its neck as he bounded onto the stage to eager audiences. When he played, he enveloped the cello with his bear-like body and tilted his head towards the scroll, becoming one with his precious instrument. The music flowed as if it came from his soul. That was my Papa that the audience knew and loved.

Papa’s music sang his sense of the beautiful, which he shared and instilled in me. I remember being in the audience as a graduate student when he played the Don Quixote cello concerto by Richard Strauss at the Casals Music Festival, as I write in the memoir:

Mehta lowered the baton and the orchestra commenced. Papa entered with a bold stroke of his bow. He closed his eyes, swayed, and transformed his cello into Don Quixote, bantered with Sancho Panza, the violist, charged the windmill, and fantasized his love for Dulcinea. I too closed my eyes and retreated within myself. Simultaneously, I became Papa, the famous cellist; Don Quixote, an idealist with illusions larger than life; and myself, a student scientist, Papa’s son, a spectator in the audience, feeling both big and small, but with an artist’s heart that only I could sense.

In the documentary film, I read excerpts about these thoughts from a draft of my memoir. Although a formidable artist and musician, like all of us, Papa couldn’t be cast into a single mold. He recalls in a radio interview in the Archive that it was the shape of the cello, not the music, that he first fell in love with, already at 5 years old. The instrument had to be as beautiful as the music, and so it’s no surprise that he concertized on a Stradivari cello. Before he received a real cello at 7, he played an imaginary cello, beautiful in his mind, with two sticks, one the vertical instrument and the other the horizontal bow.

Papa disregarded convention, not for the sake of standing apart, but because of the necessity to think independently in order to survive his tumultuous life by his wits. I believe the film will make this point. Especially important for me was his original way of thinking, reflected in the title of my memoir – The Speed of Dark:

Perhaps the most important positive influence that Papa had on me, which I doubt he realized, was his originality. He was a champion at what I call “mental gymnastics.” For example, I remember being home on semester break from college and telling him that nothing can travel faster than the speed of light, a fact I had learned in my physics class.

“Nothing?” he said.

“Nothing,” I repeated, confident of my new knowledge.

“What about the speed of dark?” he asked.A physicist would smile dismissively at such silliness. The “speed of dark” was scientifically ridiculous; there’s bright light and dim light. Nonetheless, Papa’s way of seeing the world from multiple perspectives, as a gymnast might contort his body, encouraged diverse ways of thinking. He twisted ideas creatively, turned reality upside down despite the risk of being contrary, and had a sense of humor with deeper significance than laughter.

Added to Papa’s immersion in beauty and independence of thought were dreams of lives he never lived, and these were all major influences on me, and themes in the memoir:

Runaway enthusiasm often poured from him, like his dreams to explore jungles, to search for burial grounds of elephants, or to plummet the depths of the oceans to witness its mysteries. He had often told me how lucky I was to learn so much at college, which he had never attended (he hadn’t even completed high school), and how I would have great adventures in my life. It was almost as if he envied me! Did he expect me to live his dreams?

He was correct about my having great adventures in my life, but they were born from my dreams, not his. His life can be appreciated in the Grigor and Sham’s movie, and I can’t wait to see it for myself next week and learn about some adventures in his life that I never knew.

Leave A Comment