“I hope not!” said my friend when I asked if her artistic 9-year-old grandson was taking art lessons. His pictures, especially of animals, showed maturity belying his young age, equal even to many I’ve seen by professional artists.

But what caught my attention was neither his talent nor the quality of his art, which were both impressive, but my friend’s response: no teachers please!

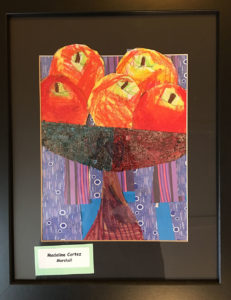

A still life created by Madeline Cortez, a student at Kensington Parkwood, an arts-integration elementary school. For their first-grade art project, the students modeled their work after one of Paul Cézanne’s Still Life with Apples.

I know what she meant. Give the kid a chance to develop an original voice. Students copy teachers as models rather than struggle with developing their own voice. I was impressed when I visited a class of artists and saw all their paintings similar in style – the colors, perspectives and brush strokes – to that of the instructor. The one or two who differed stood out, even if they may have been technically less accomplished (I couldn’t tell).

Zdenek Kostrouch, a fellow scientist interested in literature, said he liked my early short stories, but when I mentioned that I was taking writing workshops and interested in publishing, he looked distraught. “No, no!” he said. “Someday, maybe, but not now. Wait until you have written at least forty stories.” I have no idea why forty was his magic number, but that didn’t matter. It was a question of authenticity, keeping an original voice, not unlike the question of the effect of teachers on creativity. “Don’t lose your original voice,” he said. His concern was that I would bend my stories to satisfy critiques, then appeal to the market to have them accepted for publication, and both would dampen my voice, or maybe eliminate it altogether.

I’ve also heard that some writers always read several books simultaneously to guard against becoming too influenced by one style.

A common conundrum of creativity, then, is to know when to take the fork veering off the road of influence to Robert Frost’s path “less traveled by.” Isn’t shunning instruction or influence altogether a bit like putting your head in the sand? Sometimes I wonder if striving for originality isn’t the road to losing one’s voice.

Is it necessary or even helpful to hide from present knowledge – to isolate oneself – to be original? Can one even recognize originality in isolation? No voice is heard from a soundproof chamber.

I’ve never forgotten hearing embryologist Oscar Schotte at a NIH seminar almost fifty years ago say, “To make a discovery in science you need two separate ingredients: first, the data, and second, the knowledge that you’ve made a discovery.” How could you know you’ve made a discovery or been original if you haven’t encountered the contributions of others and studied the state of the art?

But then again, is it necessary or even helpful to know your voice is unique? Perhaps peers, historians, or critics would judge that better.

Relax, I say. No one can escape from his or her skin. No creative work is entirely unique; no evolution takes place without common ancestors. Great artists have copied works of their predecessors while learning and exploring possibilities for centuries. Certainly much – almost all – art was produced in environments where groups of artists influenced each other: Michelangelo and the Italian Renaissance; Rembrandt and the seventeenth century Dutch Golden Age of painters; Renoir and the Impressionist movement. Japanese art influenced Van Gogh and African art influenced Picasso, but no one considers them derivative artists without a strong voice of their own.

Repetitions are never identical and often creative. Even identical twins have small differences in their genetic makeup, appearance and behavior. Certainly no twin thinks himself or herself as redundant! Much great art exists as repeated subjects from the artist – sketches, rough drafts, self-portraits and variations on the theme. Monet’s haystacks come to mind, and Van Gogh’s copies of some of his most important paintings (i.e., the postman Joseph Roulin; the bedroom; Le Berceuse; see E. E. Rathbone, W. H. Robinson, E. Steele, and M. Steele, van Gogh Repetitions, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2013). Each repetition is unique; what a student has been taught and t is not the work of the teacher. Inuit sculptures repeat common themes over and over again: mother and child, shaman, a few myths, Arctic wildlife. Yet, each work is original if the artist is original.

Repetitions – variations and experimentations on the same or similar subject – reveal complexity as well as the numerous decisions the artist struggled with. In some ways it is like playing with context, each change emphasizing a different quality of the work. Each previous work of an artist is a teacher for the next work. Teachers are unavoidable for creativity. Teaching and learning are inseparable, as are teachers and students.

Thus, the paradox: unique works of art – original voices – emerge from collective efforts, repetitions and teachers. I doubt a teacher can block an original voice anymore than create one.

Creativity cannot be taught, but technique can. I see it lacking in too much of modern art, which does not tell its story well because the artist has not learned the tools of his/her craft, or dismisses them as old-fashioned. I am for learning how to express ideas through the use of technique which allows the observer to understand what it is the artist wishes to say.