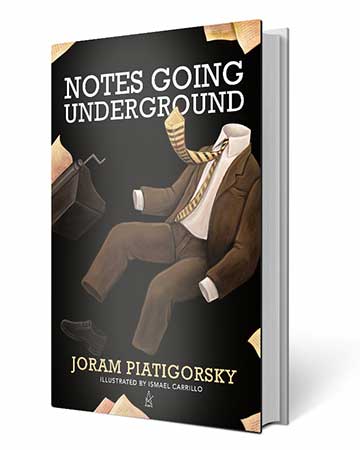

Notes Going Underground will be released by Adelaide Books later this year. Original drawings by Ismael Carrillo.

Can dead and alive occur simultaneously? The conventional answer based on science would be no, dead and alive are mutually incompatible states. Death wouldn’t exist without life, and life would need redefinition without death. Death is the final and inevitable consequence of life.

However, I have written three stories in which life and death overlap – Notes Going Underground – scheduled for publication by Adelaide Books later this year. In one story, a dead man gives his own eulogy at his funeral service as his life passes slowly into his coffin by his side; in another, a man, alive, believes he’s dead until he attends what he thought was his funeral; and in a third, a man, pronounced dead by his doctor, watches his life seep away slowly until he is buried a week later after his funeral service.

When I mentioned these stories to a friend the other day, she shook her head and said, “I have no interest in such nonsense. I don’t like fantasy or the supernatural.”

Although I’m drawn to all forms of imagination, I considered the importance of some foothold on what’s known to appreciate anything novel. Even fresh scientific insight supported by solid data will generally be neglected unless connected to an accepted structure; this is the well-known ‘principle of correspondence’. Consider, for example, the brilliant 1865 experiments on pea plants by the Augustinian friar and scientist Johann Gregor Mendel laying down the foundation of genetics. His findings needed rediscovery in 1900, when significant scientific advances had occurred, for his laws of inheritance to be understood and appreciated.

While stories are not part of cumulative knowledge and don’t require consistency as does science, there are boundaries for different genres. Fictional characters and events are not credible in biographies, memoirs or histories. Novels and short stories too are open to criticism if the events are too coincidental or improbable. In brief, personal experiences provide boundaries for acceptance even in fiction, which remain at arms-length unless we can link the story to something familiar.

But what about fantasy? Does it also require a link to reality that eluded my friend?

Since my stories on the fantasy of a porous barrier between life and death, I have considered briefly how other storytellers have dealt with the overlap of life and death in some form and the notion of the continuation of life after death.

Jose Saramago, the 1998 Nobel Laureate in Literature, opens his novel The Gospel According to Jesus Christ with Joseph thanking God for returning his soul when he awakens, for the soul escapes during sleep, mimicking death, and brings him back to life in the morning. Only faith, a religious concept, is required for acceptance of this interchange between life and death. In another book by Saramago, All the Names, a lonely clerk in the Ministry of Birth, Marriage and Death, becomes obsessed with and has difficulty in obtaining information on an obscure young woman of little note, in part because the records are filed separately for her birth and death. He concludes that the index cards for birth and death should be filed together, perhaps implying similarity of life and death.

In the novel Lincoln in the Bardo, George Saunders relies on the history of the death of Willie, Abraham Lincoln’s 11-year-old son, to bring the buried dead back to life and speak to one another in the graveyard.

In Selden Edwards’ wildly imaginative novel, The Little Book, Wheeler Burden travels from 1988 San Francisco to 1897 Vienna, where he meets his grandmother and father, as well as Sigmund Freud and Gustav Mahler. By this reversal of time reinstating the dead, Wheeler recognizes how his life relates to that of his past lineage, creating a continuity of sorts between life and death, a type of porous barrier between the two states.

In The First Man, an unfinished, posthumously published novel by Albert Camus, 40-year-old Jacques Comery (the pseudonym for Camus) stands by the grave of his father who died at 29, and feels the crumbling of the internal statue he has erected of his own identity, realizing that he is the continuation of his father’s life. I felt the same way when I recently read my father’s unpublished novel, Mr. Blok, for the first time, and was startled to learn how his mind had meandered into blending life and death, as had mine independently. Thus, I included an excerpt of Mr. Blok illustrating this to my short stories.

As for myself, I cannot resist journeys into the unknown and the fantastic, believing that boundaries are destined to be changed as our minds push them aside, but keeping in mind that fantasy is an extension of reality, often a metaphor, within the world we inhabit.

Leave A Comment