Here I blend evolution with Inuit art and shamans, unlikely cousins.

Inuit sculptures hooked me the first time I saw them. Inuit artists live in the Arctic of central and east Canada. Although Inuit art is a known form of ethnic art, few appreciate its beauty, originality and significance. I happened upon it 25 years ago, in an Alaskan art shop in Vail.

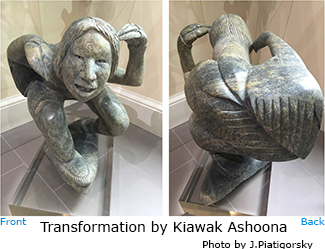

Is it a man transforming into a bird, or is it a bird transforming into a man? Ambiguity is a hallmark of Inuit art.

I have been an avid collector ever since. At first I was attracted to the technical skill of the artists and, especially, the movement inherent in the carved stone. As I collected I was drawn to the stories, humor and imaginative voices that the diverse sculptures expressed. But it took longer for me to sense their connection with evolution. The carvings of shaman, especially, resonated with and added a new, artistic way to express evolution. Who would have guessed? Art and science: two for the price of one.

Why shaman? A shaman is a person with magical powers and is represented in many cultures and forms of ethnic art. A medicine man – a doctor who heals with magical powers – is a shaman, and a person who sees what others cannot is a shaman. The shaman trait that most struck me, however, is the ability to switch – transform – from one species to another. This opens innumerable ways to portray a shaman artistically. Inuit artists create shaman sculptures that are chimeric animals, including of course, man. These shaman sculptures are called transformation pieces.

The two photographs – front and back – of a transformation sculpture by Kiawak Ashoona (Cape Dorset, Baffin Island) shows a shaman with one hand a crab-like pincer and the other hand a type of claw; this crouching shaman also has wings on its back, as if transforming into a bird, or is it a bird transforming into a man? Ambiguity is a hallmark of Inuit art.

Shaman with Bird Hands, by George Tatanniq (Baker Lake, Nunavut)

Another sculpture shown here by George Tatanniq (Baker Lake, Nunavut) is a shaman with bird hands. Inuit artists have carved dozens of different chimeras representing shamans. Charlie Ugyuk (Goa Haven, Nunavut) carved an imaginative and complex shaman shown in another photograph here. Note the eyes protrude from the head, and this presumably indicates that the shaman has powers to see “outside of his body.” There is no shortage of imagination among the Inuit.

I used a shaman sculpture as the frontispiece for my book on gene sharing for an artistic interpretation of the gene-sharing concept, i.e. borrowing and blending traits for multifunctions. The legend of the frontispiece reads as follows: “The expressive bird-shaman Inuit carving by Tommy Sevoga (Baker Lake, Nunavut) illustrates the artistic impact of placing familiar body parts in a foreign arrangement. The fusion of a human face, animal ears, and a bird body has created a shaman possessing greater powers than the living forms from which the parts were derived.”

For me, these transformation Inuit sculptures resonate with biology and express, with unique poetic license, the continuity of diverse species, giving a snapshot of evolution at a single time point.

Leave A Comment