The reporter clenches his jaw.

“You asked for a neutral site without publicity. You didn’t want me to come to your house or office or restaurant. A commercial real estate agent let me use this place. It’s a dump, but it’s the best I could do.”

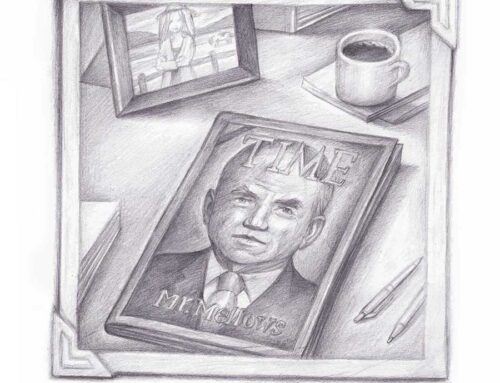

“I like it,” responds Mr. Mellows, who finally reveals that he’s capable of smiling. He looks lingeringly at the farm girl.

“About your parents,” the reporter says, trying to refocus the interview. “Were they also in business?”

“Heavens no! My father was a molecular biologist, may he rest in peace, and my mother worked for a tree company.”

“A tree company?”

Mr. Mellows thinks a moment. “Yeah. She was tiny, only 4-foot 7, and loved to climb trees, heaven knows why. She didn’t weigh enough to break the small branches, so she was able to get to places that are hard to trim. Most of her work was on the estates of rich guys.”

“Pretty dangerous. Did it teach you to take risks like you’ve done in your work?”

“You bet, except that she fell off a tulip poplar by a tennis court on her fortieth birthday and bye-bye. I was 12. That made me the only child of a single parent. My dad told me to get used to it; nothing lasts forever. You might write that down. He was tough.”

“Wow! Quite an experience for a 12-year-old.”

The reporter scribbles ‘nothing lasts forever, tough father’ on his pad.

Mr. Mellows puts his left hand in the pocket of his gray cotton pants; coins jingle. He loosens his maroon tie and undoes the top button of his shirt, crisp white except for the symmetrical grey discolorations under his armpits.

The reporter wipes his brow. “Your father must have been a big man to have a tiny wife and a huge son like you.”

“Not really. He was about 5-foot 10 at a stretch. Don’t ever try to psyche out nature. It’ll fool you every time. Nothing’s predictable. That’s been a guiding principle of mine. You can write that down too.”

“Yes, sir.”

The reporter writes on his notepad ‘nothing’s predictable, guiding…’ He stops writing before finishing and looks lost in thought.

“Hello?” says Mr. Mellows.

“Sorry.”

The reporter asks another question.

“Was your father a well-known scientist? That is, were you exposed to fame as a youngster?”

“Hardly, although it depends on what you call fame. Most of the people in his building at work knew him, as did a dozen or so scientists around the world. He got an award once, from a pharmaceutical company. No, it was from an entomology society. He studied sticky stuff on the bottoms of the feet of certain kinds of bugs. I forget their scientific name. Busted his ass and sweated every detail of his work, and nobody cared, except a few peers. They argued like crazy as to who discovered what first. Man, it would make a boring movie! Watching him taught me a lot about life, even though it sort of broke my heart.”

Mr. Mellows hesitates. “Science is fascinating though. Something about it that’s…well…that rings true…” He looks sad and then adds, “Science doesn’t depend on perception to be right.”

“Is that what you learned from your father?”

Mr. Mellows checks his gold Rolex and then stares at the print on the wall.

“Mr. Mellows, what did you learn from your father?”

“Yes, yes. Excuse me. She’s so pretty. I mean, really charming. Like the girl with a pearl earring by Vermeer. Know that painting?”

“Yes, sir.” The reporter looks at the print and then returns to his question.

“About what you learned from your father. What was it?”

“Give awards, don’t get them. The percentage is much higher, and everybody else waits on the edge of their chair rather than you. Makes you far more important, and you don’t have to say thank you or grovel explaining how you don’t deserve it, that it’s all due to others, and…well.”

The reporter scribbles some notes, underlines a phrase.

“Mr. Mellows, how did you make USC so financially successful and innovative? The use of large sheets of pliable, green steel that’s comfortable to walk on, like grass, and generates energy from soil heat. That was brilliant! How did that come about?”

Mr. Mellows stands up and paces the room. He sneaks a look at the farm girl again, whispers inaudibly to himself and turns to the reporter.

“The first thing I did when I took over the company is strip titles from everyone. Hierarchy stifles creativity. It helped morale and ideas flowed like water. A green, soft, energy-producing woven steel grass substitute was just one of the ideas, and it came from a new recruit. Young people are too foolish to be cautious. You’re young. Know what I mean? Do you take chances?”

Leave A Comment