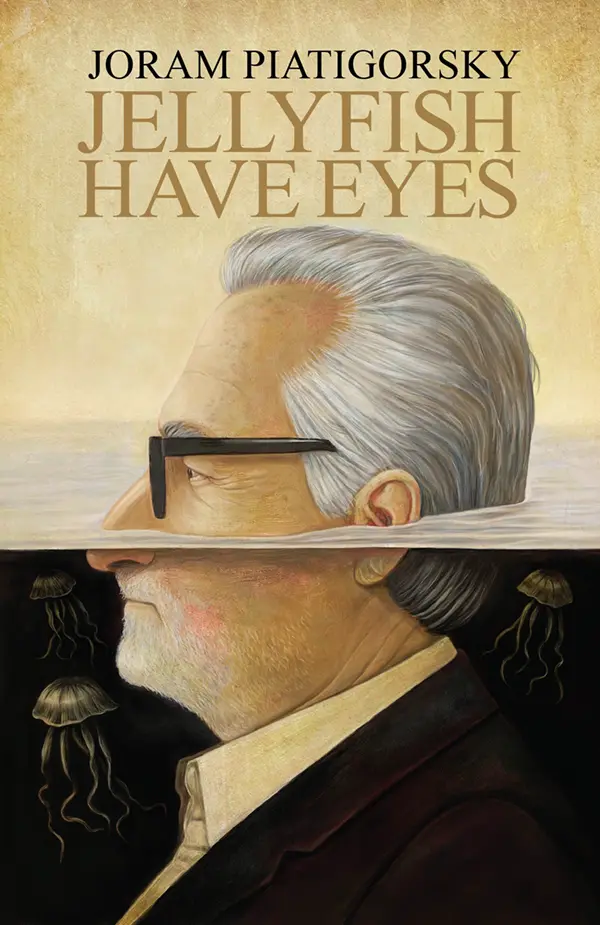

This is the story behind the story. The event that sparked a creative exploration which resulted in a scientist becoming a novelist.

Some twenty-five years ago in the mid-1980s, midway through my fifty-year career in vision research, I learned that jellyfish have eyes. At the time I was chief of the Laboratory of Molecular and Developmental Biology, National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland. My specialty was gene expression in the eyes of vertebrates, especially chickens and mice. One Saturday night I settled into my favorite chair with its worn, leather skin darkened from age and opened a book I’d bought on invertebrate vision. “Time to learn something new,” I told myself.

I skimmed through the first few chapters filled with boring classification schemes devoted to the diverse compound eyes of insects, the most famous of which is that of the fruit fly, Drosophila. As I ploughed on reading, suddenly a life-changing moment arrived, unannounced by trumpets or fanfare but by the quiet turning of a page to the chapter on eyes of Cnidarians, the invertebrates that include corals, sea anemones and jellyfish among other more esoteric animals such as hydroids and sea pens. Cnidarians are almost as ancient as sponges. Most cnidarians are plant-like animals stuck to the ground and don’t have eyes. But jellyfish are a different story. There are a variety of different jellyfish with life cycles that alternate between a sessile poly phase and a sexual, swimming medusa phase. I was amazed to learn that the cubomedusan jellyfish (known as box jellyfish due to their symmetrical shape) have sophisticated eyes. I stared in disbelief at the pictures of the complex eye of the jellyfish medusa. What most people consider slimy globs that sting if you touch them (the painful sting of the notorious Australian box jelly can be lethal) are actually animals that can see!

The complex jellyfish eye looked like a variation of the highly evolved human eye. The front of the eye had a large lens for concentrating and focusing light onto the retina (the light sensitive photoreceptor cells) in the back of the eye. Lens-containing eyes with this type of anatomy are known commonly as camera-type eyes. Despite that I had studied eyes for twenty years, I had no idea that jellyfish could see anything, much less had sophisticated eyes. I doubted whether any of my colleagues knew either, although it turns out that the jellyfish eye had been discovered already in the nineteenth century. I guess we all live in a miniature black box of ignorance that conforms to the landscape of our peers. I had an urge to break out of that box.

The pictures in the book showed one larger and one smaller jellyfish eye facing different directions on specialized structures called rhopalia. Each jellyfish had four rhopalia equally spaced around its circular surface, called a bell (which I found strangely ironic for such a silent, non musical structure); each rhopalium dangled from a stalk within a cavity open to the seawater. It would be impossible to hide from one of these round creatures that see simultaneously in so many directions, a remarkable adaptation for their three dimensional, liquid environments. In addition to the camera-type eyes, each rhopalium had four other so-called “simple eyes” (two roundish and two slit shaped) that had light-sensitive photoreceptors but no lens. That wasn’t all: each rhopalium had a “balancing” organ called a statocyst that let the jellyfish sense up from down. How amazing that the jellyfish – a so-called “primitive” animal (nothing could be further from the truth!) – squeezed all that sensory complexity into tiny rhopalia only about two hundredths of an inch in diameter.

Jellyfish eyes seemed much more than evolutionary stepping-stones to vertebrate eyes; they were small jewels. Jellyfish, 99% water, low on the totem pole of peoples’ interest, considered mere nuisances, were extraordinary, biologically advanced animals. Were statocysts like our inner ears? Did jellyfish “hear” anything? And, what did they see? How different were jellyfish eyes from our own? And what did they use for a brain to interpret what they saw? So many interesting questions.

![]()

I suddenly, impulsively, wanted to study jellyfish eyes. Stepping into the strange universe of jellyfish resonated with the excitement I had in choosing a career in biology many years earlier. The notion of casting light on neglected shadows of knowledge rather than wiggling into the sunbeam of present interest – hopping on the “bandwagon” as it’s called in conventional jargon – was enticing. To be honest, I felt that there was not only scientific validity in performing research on jellyfish eyes – to be led by curiosity – but that there might be glory too. Who could tell what camouflaged treasures I might find by illuminating dark corners of Nature? I imagined that understanding the secret of jellyfish eyes beneath the surface of the sun-drenched sea might have as much potential value to humans as uncut diamonds have potential brilliance. My poetic Lord Byron self, always colliding with my analytical Louis Pasteur self, merged to form one giant wave in my heart: I saw jellyfish as a poem and their eyes as a laboratory.

Tripedalia cystophora Image courtesy of Jan Bielecki; Alexander K. Zaharoff, Nicole Y. Leung, Anders Garm, Todd H. Oakley (June 2014)

How to go about studying jellyfish? I perused the scientific journals and found an article on jellyfish co-authored by a person called Charles Cutress at the marine laboratory in La Parguera, Puerto Rico, which was a part of the Mayaguez campus of the University of Puerto Rico. The article had been written a few years earlier but a quick check established that he was still at the marine laboratory and so I contacted him. He responded enthusiastically to my inquiry and said that he would teach me how to capture the local cubomedusan jellyfish, Tripedalia cystophora, and let me work in his laboratory if I would like. Of course I would like! What an adventure. I immediately called my close friend and colleague, Joseph Horwitz (a professor at the Jules Stein Eye Institute at UCLA School of Medicine in Los Angeles) and asked him if he wanted to join me. He agreed and off we went not sure what to expect.

After landing in San Juan, Joe and I rented a car to drive to La Parguera, still just a name to us. The humidity melted the obligations of my daily life: the irony of being liberated from the chains of having achieved my childhood dream to have a successful research laboratory. Although I loved science and my work at the NIH, an invisible vice loosened its grip as we drove through the lush vegetation of the tropical rain forest, away from politics and NIH, pursuing jellyfish; jellyfish eyes of all things!

“Great to be away from everything for a few days, eh?” said Joe as if he were reading my mind. Perhaps it was his tone of voice, perhaps it was my sense that he viewed this trip as a vacation instead of the serious scientific endeavor that I considered it, but I began to question my excitement about studying jellyfish eyes. There was a difference between an idea – an impulse – and its reality. What was I looking for? Was there any possibility for success, especially when the goals were so fuzzy? I didn’t even know if we would be able to remove the eyes from the jellyfish, or if this Charles Cutress was at all reliable. As we drove, however, I decided that sometimes it’s best not to question too much. There was no point in trying to see through an opaque screen or to predict the mysterious unknown. In any case, how does one define success in the acquisition of knowledge? I relaxed and let time decide how this trip would develop. We passed a small series of run-down shacks. A few men sitting on porches with doll-like faces rotated their heads following our car as it whizzed by. I wondered how much they questioned in their lives or how many chances they took on a whim. Abandoned junk, used vehicles, spent tires and other trash were eyesores along the roadside. We were in a different world from our daily lives and I liked that. Maybe I could break out of my black box.

Eventually a small sign announcing La Parguera appeared on the side of the road. A hotel and bakery marked our entry into the small town. I turned right onto the main street and drove past some small shops and a central square dotted with people, young and old, in T-shirts and shorts and sandals. They looked comfortable and at ease. Scuba gear for sale or rent in numerous places and the absence of foreigners indicated the importance of local tourism. After a few blocks we found the small motel that Charles Cutress had booked for us. It had a wooden outdoor bench attached to a picnic table in the back patio by the bay; funny how one remembers small details of little importance after many years. After settling in our shared room, we explored the town. It didn’t take long until we virtually dripped with sweat from the oppressive July heat and humidity. Stray mutts, bone thin with dirty knots of hair substituting for fur, wandered aimlessly sniffing for morsels of food.

“Pathetic, isn’t it?” muttered Joe. “The stray dogs are like walking rib cages.”

No one in the streets seemed bothered about the dogs or anything else. The open doors and windows of the shops and restaurants distributed the heat democratically between the outside and inside with air conditioning limited to a few noisy window units here and there. We reached the center of the main square where people congregated, strolled, rested on benches, ate junk food, laughed and danced on Saturday nights and holidays. Colorful graffiti and art by gifted, local artists decorated the walls of the buildings. Joe and I both remarked how sad it was that our busy, rushed way of life in our respective cities had lost that streak of humanity bathing tiny, foreign La Parguera. It made Joe nostalgic since it reminded him of Israel before he immigrated to the United States in the 1960s. Sometimes less is more.

A rooster serenading us from somewhere outside awoke us early the next morning. After a brief breakfast of dry cereal and coffee sitting at the outdoor picnic table of the motel, we headed down the main street to the other end of town where a small boat ferried us to the marine station located on an island, a two-minute hop from the mainland.

“Good grief, are we in Jurassic Park?” I exclaimed when stepping on the dock of the island of the marine station and seeing a large iguana waddle by. I looked around and saw more of these prehistoric-looking reptiles roaming about. It was like moving backwards in evolution to pursue new knowledge, a good omen for my efforts to learn from the ancient jellyfish. I liked the odor: the salt air, the humidity, the smell of the sea. We made our way from building to building until we found the one in which Charles Cutress worked.

“Pretty quiet here,” said Joe as we entered the building. I agreed with a grunt. We went down the hallway until we found the laboratory with his name on the open door and walked in.

“Hey there! Joram? Is that you? Joram Piatigorsky?” said a voice from a small office in the back. A stout man, sixtyish, round face, graying, wearing tennis shoes, white shorts and a yellow T-shirt stepped out.

“Dr. Cutress?” I asked.

“Not doctor; just ole Chuck Cutress. I never did get my Ph.D. Good to finally meet you.” He had kind eyes under bushy eyebrows. I liked him.

“Same here,” I said. “This is my colleague, Joe Horwitz, the person I told you was going to accompany me. Thanks for arranging all this for us. We got in yesterday evening. The motel’s perfect. We’ve looked around town and are ready to get to work. Cute little place.”

“Cute? Yes, maybe. They say a hurricane is brewing off the coast of Africa and may drift this way.” Chuck glanced out the window. It was cloudy, but not threatening.

“Let’s hope it changes its mind,” piped up Joe, taking in the glass bowls on the bench tops for holding aquatic specimens and the antiquated dissecting microscopes and the labeled, alcohol-filled jars of fixed invertebrates on the shelves.

“So this is the lab?” Joe volunteered as if he were sight seeing.

My mind focused on jellyfish and their eyes. I had many questions: how difficult was it to capture jellyfish, how big were their eyes and was it hard to dissect them? “Can we get started pretty soon?” I asked after some small talk.

“Yup,” said Chuck. “I’ve reserved a boat to go out on the mangrove to catch a few Tripedalia jellyfish this morning, to make sure we get some before the hurricane.”

“You said it’s just starting in Africa, didn’t you?” Joe asked. “That’s pretty far away.”

“That’s right. You never know though. Things change fast around here.”

I rolled my eyes and started looking through an open textbook on marine biology that was on the bench top in front of me, probably left there by a student. Each page contained images of exotic species, at least exotic to me. Some were familiar, such as starfish, sea anemones and lobsters, but some were foreign. I was impressed with their diversity.

“It’s getting dark outside,” said Joe.

Within a few minutes the bay darkened with lightning in the distance followed by ominous rolls of thunder.

“See what I mean,” said Chuck. “But this will blow over pretty quickly I think.” The sky cleared as if by magic ten minutes later.

“Let’s go,” said Chuck. He snatched several bottles of water from his desk drawer and three small dip-nets with long handles to capture the jellyfish. He walked out the door more rapidly than I thought he could move. Joe and I scampered behind.

Could one even do one’s best work if one wasn’t having fun?

Chuck skillfully guided the small outboard motor boat along the edge of town. Houseboats were docked along the shoreline; ragged-looking people sat on deck doing nothing much in particular, perhaps enjoying the sunshine that followed the cloudburst. Once again, I was impressed at how many ways there are to live a life.

“Who lives in the houseboats?” I asked.

“Squatters: people who don’t pay taxes,” Chuck answered.

“And nobody says anything about that? They live in peace?” asked Joe.

“Well, they don’t make any money and they’re not living on land, so yeah, they’re just enjoying life.”

I was enjoying life at that moment. The wind swept my face, the sun warmed my body, and the gentle bounces of the boat against the choppy waves were comforting, like being rocked to sleep. I closed my eyes. Cherish the moment. This is what life’s about: feelings, not thoughts, I said to myself.

Suddenly the sound of the motor dulled. Chuck had slowed the boat. I opened my eyes and found myself in a protected cove surrounded by mangrove trees with thick branches from which roots projected into the flat, shallow water. Algae coated the roots of the mangrove trees beneath the water and crabs crawled over the branches. Life was teeming everywhere in its different forms. I looked behind the boat and saw the narrow entrance we’d gone through to enter the lagoon. Off to the left there was another narrow canal that led to another lagoon lined with more mangrove trees, and beyond that there were more lagoons and more canals. The brackish waterway twisted among small islands and inlets. I was amazed at this visual paradise and extended labyrinth so close to the town with its sickly dogs and illegal houseboats. It reminded me how a fancy residential neighborhood is often situated a few city blocks from a business district or even a ghetto.

“Can you remember what it’s like back home?” I asked Joe. “The busy streets, the mass of people, the ridiculous rules we live by day in and day out?”

He didn’t answer.

“Can get nasty in here,” said Chuck. “Lots of mosquitoes this time of year. Hot too.”

“It’s fantastic,” I said.

Joe scratched his neck.

Chuck headed the boat directly into the thick mass of trees. We ducked our heads and dodged the sharp branches. When the boat was crammed between the trees, Chuck put the motor in neutral. Only the chug-chug-chug of the motor upset the peace.

“Ok, let’s collect. This looks like a good spot,” said Chuck as he took one of the two buckets he’d brought, filled it with seawater by dipping it over the side and placed it back on the boat. “This should hold our catch.”

I turned to Joe and said, “He’s an optimist!”

Chuck taught us to recognize the jellyfish as they swam by the boat in jerky motions propelled by regular contractions of their translucent (almost transparent) muscular surface bell. The largest jellyfish were only a fifth of an inch in diameter. The swimming medusae had separate sexes. Orange embryos appearing like dots swarmed within the cavities of the inseminated females. The males had several vertical white streaks of testes beneath the surface of the transparent bell and were easy for even a novice like myself to distinguish from the females. Fertilization is internal in these animals; the males release packets of sperm looking like missiles that enter the females. Free-swimming larvae are released from the females and transform into tiny anchored polyps that later metamorphose into swimming medusae: medusa, larva, polyp, medusa, larva, polyp, throughout endless generations. Scientists have estimated that jellyfish appeared in evolution six to eight hundred million years ago. I felt like a newcomer on the planet.

“These jellyfish are hard to see in the water,” I said.

“You’ll get the hang of it,” answered Chuck. “You can detect them when they cross the streaks of sunlight filtered through the leaves on the trees and entering the water as clean pencils of light. Have patience.”

He was correct. The short jellyfish tentacles reflected the bright lines of sunlight that penetrated the water. Chuck expertly scooped out jellyfish one by one with the dip-net and dumped each into the bucket; soon Joe and I were doing the same, but more slowly and with less skill. As difficult as it was to see the jellyfish in their natural habitat, they were obvious in the bucket, where they swam aimlessly rather than in straight lines as they did in the wild. There was something sad about yanking these innocent animals away from their home like they were criminals; what had they done to deserve such a fate?

“Do you think these jellyfish have any destination in the lagoon?” I asked. “Sometimes they’re heading down to the bottom, while other times they’re going full speed ahead as if they’re late for an appointment of some sort.”

“You’ve got to be kidding! They’re gobbling up whatever food they find,” Chuck answered.

“When you get back to the laboratory, put them under a dissecting microscope and you’ll see tiny crustaceans or even small fish in their stomachs.”

![]()

I began to appreciate the strength and resilience of these ancient aquatic animals. The jellyfish were not docile, peace-loving animals; they were hungry predators. Their delicate appearance was misleading. Only the most robust species survive the eons of time of evolution. The stultifying humidity, the buzzing mosquitoes with their unquenchable appetite for human flesh, and the threatening branches jutting over the water reminded us that Nature does little to please its inhabitants. And man does little to please Nature, I thought.

It was a special day for me, the kind that I’d dreamed about in my government office during the long gray winters in Bethesda. Here I had no interfering bureaucracy, interruptions by students and colleagues or seminars to attend. No one would ask me for anything for the next few days. It was glorious just collecting jellyfish in their lush, brackish environment, to feel a part of the hugeness of Nature without doing anything to deserve it. I wasn’t a government scientist and laboratory chief at that instant; I was a free ghost of myself that had escaped its protective shell. I wondered how many ghosts lived in me and what conditions would release each one.

I stared at my reflection on the water surface to confirm it was really me on that boat, trying to convince myself that it was all right to enjoy my work, to treat it as a vacation. There was no rule against that. Could one even do one’s best work if one wasn’t having fun?

A speedboat dragging a water skier rushed by and created waves that caused water to spill from the bucket holding the jellyfish. Iridescent gasoline glistened on the water behind the speedboat and loud, metallic music disrupted the quiet setting. My image in the water disappeared in the turbulence. I was back on earth.

Chuck glanced at his wristwatch. “I think we should head home,” he said. “We’ve been out here a long time and frankly, I’m tired and still have work to do.”

Joe jumped in and volunteered, “Agreed.”

I nodded but felt squeezed by limited time. I didn’t want to leave this secluded haven. We had only a few days at La Parguera. My knee bumped on the side of the boat as I moved clumsily to the center seat preparing for the short ride back. The irritating music from the tourist speedboat dissipated in the distance and the water calmed; the scenery looked the same as it did before, except tranquility had submerged into memory.

“Have a good life,” I said grandiloquently to a solitary jellyfish cruising by, and then my eyes shifted to the dense collection of jellyfish in the buckets. Pretty good haul, I thought with pride. I’d become a collector of jellyfish and had acquired a new skill. Then I asked:

“Do we have time to take a quick look on the other side of the waterway. There should be a bunch of jellyfish there. ” I guess I was getting greedy.

“Never seen one there or anywhere else in the mangrove but this spot,” said Chuck, surprisingly.

“How’s that possible?” Joe asked.

“I don’t know,” answered Chuck.

Intrigued, Joe and I insisted on scanning the opposite side of the lagoon for jellyfish, at least for a quick look-see. Again, Chuck was right: we didn’t find a single jellyfish. Confused, I persuaded Chuck to go around the corner to a different opening between the clumps of mangrove trees, and after that to still another site. Although all the areas looked identical to me, we didn’t see a single jellyfish. The jellyfish community formed a tight clique that didn’t extend into other zones. Or if it had at one time, the members had been wiped out. If that were the case, I wondered why or how. The only natural predators of jellyfish that I knew of were turtles (and now me!). I imagined battles between groups of jellyfish from neighboring sites that exterminated each other.

“Strange,” I said.

Joe nodded in agreement.

We decided to head back. Chuck looked relieved to be returning to the laboratory and Joe seemed tired, as if he’d had enough for one day. My mind, however, was bouncing between fanciful images of hierarchical jellyfish societies and scientific questions concerning jellyfish vision, behavior and ecology. What’s the story here? How many different stories are there? I wondered. I was straddling the gray terrain between fiction and science searching for how to fill in the blanks.

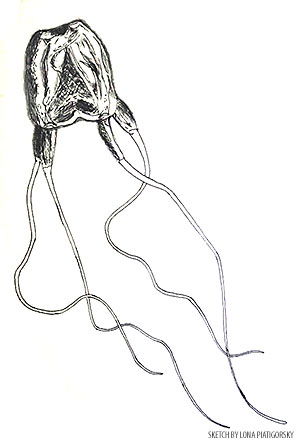

After two days of successful hunting for small Tripedalia in the mangroves, Chuck told us about another species of cubomedusan jellyfish with complex eyes. Carybdea, whitish with long tentacles was three or four times larger than Tripedalia, could be caught at night from the dock of the marine laboratory by shining an incandescent light onto to the surface of the water. The jellyfish were drawn to the light; exactly how or why wasn’t known, but clearly the eyes were involved.

Drawing of Carybdea by Lona Piatigorsky

We decided to try our luck hunting Carybdea on our last night in La Parguera. After sunset, wet from the humidity, we made our way down the sloping path from the laboratory to the dock. Joe scooted ahead carrying the light; I ambled behind breathing in the lush air. The moonbeam vibrated on the water and split the distant bay into complementary halves. The tree-lined inlet looked harmless, a post card. I imagined drama beneath its soft skin: sharks attacking seals and turtles prowling for jellyfish. A prehistoric-looking iguana walked across my path as if time had rolled back millions of years. Fireflies sparkled here and there. Flashes of bioluminescence danced on the surface of the bay. At that time I had no idea that these flashes emanated from a jellyfish green fluorescent protein for which Osamu Shinomura and Martin Chalfie would win the 2008 Nobel Prize in chemistry, shades of dispassionate Nature merging with human curiosity. Experiencing this carefree paradise in the soft moonlight where human sensibility blended science and art made me sad that I had to leave the next day. I wanted to write a poem about time and place and pondered, not for the first time, whether I had chosen the wrong career. But if I’d been a poet or novelist or other form of artist, I reckoned I would have fantasized about being a scientist, like I did when I was young and felt there was nothing more remarkable than Nature, especially biology.

The idea of justifying my trip to study jellyfish to the Director of the National Eye Institute where I worked seemed ridiculous, almost childish, like trying to explain the meaning of Frost’s poem, The Road Not Taken. I was impressed how quickly I’d adapted to La Parguera and then reminded myself that it would fade into the distance just as quickly when I returned to my regular job. La Parguera had to be seen and heard and smelled and touched to remain alive within me; memories have a way of fading and being modified by new experiences. It was disturbing in its own beautiful way that the environment was as integral to me as my organs. Did that mean when the surroundings change, so does the person? Was anything permanent in my life?

“Come on, Joram,” urged Joe, who had reached the dock and was looking for an electrical outlet for the light we needed to catch Carybdea. “Hurry up.”

“Coming,” I answered. When I reached the dock it looked different than during the busy day. The small, empty boats lined up neatly ready for the next day’s chores and rocked gently with the ripples. The boathouse was locked like an abandoned shack. Stray cats patrolling with occasional meows kept a respectful distance from us. This was the night version of the marine laboratory. Things look and feel different after the sun sets.

Joe found an electric outlet next to the research boat moored by the dock used by the investigators and students in the marine laboratory to collect specimens. He plugged in the lantern and directed the light beam onto the water surface. We sat down to eat our sandwiches for dinner, engaged in small talk, and waited for the jellyfish to appear. Dozens of small fish swarmed into the spotlight almost immediately. Squid darted in and out of the bright patch with astounding speed, visible one instant, their arms giving the illusion of a rotating propeller, gone the next. I had never seen any living thing move so fast. We waited for jellyfish. Hours passed. Close to midnight we stared into our empty bucket prepared to receive the captured jellyfish.

“Too bad,” said Joe. He didn’t sound as disappointed as I felt. He seemed to enjoy the quiet evening in the moonlight.

“We tried,” I responded, having no choice but to accept fate. “At least we got lots of Tripedalia the last couple of days. We’ll pack up tomorrow morning and catch the plane in the afternoon. We might as well get some rest.”

“Hey, what’s that!” exclaimed Joe when he took one last look at the lively crowd of fish trapped in the light.

An angelic white form with lace-like trailing tentacles, a single jellyfish, was rising from the depths. I watched transfixed by its majesty. Why had it taken so long to attend the party? Did it live directly below the dock or had it traveled from afar? How far? What did it expect to find at the water’s surface? And most importantly, what did the jellyfish see and what would it do with the information? I dipped the net into the water and gently scooped it up as it was making a U-turn to head back down to deeper, safer water. Five more jellyfish followed within as many minutes. We scooped up each and placed it in the bucket.

One never knows. Strange, I thought, making a mental note that, as I had noticed with Tripedalia, jellyfish seem to travel in groups as a team or family of sorts. I wondered how they were communicating with one another, if they did at all.

No more jellyfish appeared during the next fifteen minutes. Joe unplugged the light; we took the bucket containing the six jellyfish to the laboratory and went back to the motel. In the morning we would excise and freeze the jellyfish eyes to take them back to our laboratories for analysis.

I should have been tired after a long day in the mangrove followed by hours of waiting by the dock at night, but I wasn’t even sleepy as I lay in my motel room bed. I felt elated and energized, as if I’d just witnessed a great event in the privacy of a royal theater. The hours of waiting evaporated from my memory. All I could think about was the beauty and mystery of the jellyfish when they rose to greet us. Those few minutes expanded to fill the evening.

How does one define success in the acquisition of knowledge?

Finally, exhausted, I closed my eyes and imagined that I was floating in a boundless universe, gravity be damned, and my consciousness drifted into the vast space of nothingness. I succumbed to sleep feeling buoyant as if I were underwater among the jellyfish and dreamed them saying in a silent, foreign language, “We are alive.” The sensation was quieting and irresistible. The jellyfish propelled themselves with contractions of their body wall, but they also gave the sense of gliding effortlessly. It was as if they were heading to a known destination yet drifting passively at the same time; they were impossible to grasp, like mercury, and slipped through my fingers when I reached out to touch them. Many jellyfish streamed from the edge of nowhere into my dream, forming a rhythmic community. Some escaped and returned to nowhere. They looked alike yet each was an individual, completely alone. Some jellyfish were large – adults – others small like children. They dissolved and reformed, over and over again, dissolving and reforming, and then merging together and separating. They invaded my sleeping mind, taunting, teasing me.

I also dreamt of abstract forms of a rich fauna, including sponges and corals and sea anemones and starfish and sea urchins. The various species clumped with their own kind, although mavericks trespassed into foreign territories here and there. One wondrous, plantlike, feathery sea pen lifted magically from its stationary spot and started writing in the water as a quill dipped in dark blue ink with no hand to guide it. The words dissolved like a book telling a secret story.

I awoke with contradictory feelings of euphoria and angst. I tried with difficulty to relate my dream to Joe at breakfast. “It’s all a blur,” I said finally, frustrated that I couldn’t be more accurate. Dreams are so often that way: memories and yet not, images without explanations. “Maybe the details don’t matter,” I said. “It was strange. I seemed as meaningless underwater with the jellyfish as they would have been on land with me. But it was restful and beautiful and seemed natural.”

I’d been introduced to jellyfish: to their beauty, to their mysteries and to their isolation from anything to which I could relate. Now I could turn my attention to trying to understand their extraordinary eyes. I was ready to enter a new phase of my life in biological research.